Visiting IBJ offices in provinces was something I eagerly awaited. My first visit was to Takeo where IBJ established its first provincial Defender Resource Centre (DRC). I was especially looking forward to meeting our legal fellow at the office, Po Vannophea, who I heard was seriously injured due to an accident. I heard the story that Vannophea went to represent clients in court even with an injured leg following the accident. My first stop upon arriving in Takeo was the prison. I met the Director of the Takeo Prison, a very kind and pleasant man, who has been managing the prison for last 27 years. He remembered me from my last visit and welcomed me warmly. We sat in the wooden chairs outside his office and conversed. I could see the same blackboard where basic prison statistics were being updated daily.

The Director happily accepted donations IBJ made to the prison office as well as the health clinic. We donated some paper for the office and basic medicine such as paracetamol. While talking with the prison director, IBJ lawyer Po Vannophea joined us in conversation. He looked well despite being treated for his leg injuries the previous day. We discussed the situation of pre-trial detainees in the prison with the Director. He was glad that we now have a lawyer present in the province to assist prisoners and detainees. I then asked him about a particular detainee I had seen during a visit the previous year. This particular prisoner is a completely mute person who has been in pretrial detention for five years. I did not remember his name, but I remembered his story and wondered if he was still housed in the same prison facility. He was previously in a prison cell shared by another 80 or so inmates when I met him last year. When he finally raised his head and our eyes met I saw a thousand expressions in his eyes asking for help in some way, shape, or form. He looked dejected, lacking morale and hope, and his eyes were begging for help to get him out of the misery he was living in. When I asked the prison Director about him during this visit, to my disappointment, the Director told me that he is still in the prison and that the court was eventually planning to release him upon the receipt of a pardon from a higher authority.

When I told the Director that I would like to see him, to my surprise, he pointed his finger at a person wearing a hat who was working outside the prison, helping to build a wall between the prison compound and adjacent government offices. Upon seeing him I was not sure if he remembered me, but I certainly remembered him. When he was summoned to the dilapidated office of the Director, he looked very different from last year when I saw him. He actually looked energetic and hopeful. There was no dejected expression on his face and he was smiling at me. I seized the opportunity and took a photo with him, wanting to capture that moment and remember it for all time.

The only way that I could communicate with him was through eye contact, and after exchanging a few meaningful glances he then went back to work. After my meeting with the Director, I saw my old friend in the distance who had resumed helping to build the wall – again, he looked at me and I waved my hand in return. To my pleasant surprise, he smiled and waved his hand in return. I told the IBJ lawyer in the province to closely follow his case and do whatever possible to get him released, as there have been no charges against him during last six years, and he lacks the ability to advocate for himself because he is completely mute. I also later learned about the sad irony this particular prisoner is facing. His wife has become mentally unstable and if he is released he will not be able to return to her. As there is a severe lack of rehabilitation facilities for persons with communication disabilities like him, I am now wondering what challenges he will face once he is released.

After visiting this prison, I visited the Takeo Provincial Court and met with my good friend, the Deputy Prosecutor. When I first visited Takeo in August 2007 and met him, his profound words struck me. He requested that IBJ start an office in Takeo and place a full-time lawyer to defend accused persons. He told me that as a conscientious and law-abiding prosecutor, he could not allow defendants to come before the court without a lawyer representing them. He was very direct and genuine in his expressions, and his appeal to IBJ was straightforward and honest. I remember this moment vividly and later conveyed this episode to the WISE Partnership representatives when IBJ was looking for their assistance in funding the Cambodia Program. When I met him this time, I reminded him of our conversation with him and his appeal to me several years back. He told me that he is very happy that now IBJ has a placed a lawyer in the Takeo province in an effort to assist in the defense of accused persons.

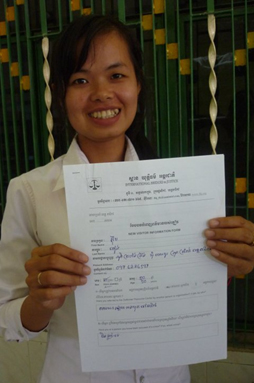

Later during the day I was again talking to Po Vannophea, IBJ’s Legal Fellow at the DRC in Takeo. He has not fully recovered from his accident, but he was beaming with enthusiasm and energy. He looked like a very confident and competent young lawyer ready to face any challenge. I was then telling him that funding for the Takeo DRC as well as other DRC’s in two other provinces will be guaranteed until the end of 2010, and that IBJ will be actively looking for funding opportunities this year for 2011. He then said, “If IBJ’s office closes down, I will not go back to Phnom Penh to look for a job. I will practice law in the Takeo province and continue to assist people here.” This statement is extremely significant as it relates to the overall nature of legal practice in Cambodia, where the trend is for young lawyers to move to Phnom Penh to earn higher salaries and practice corporate law. I guess most law student in the world tend to have similar plans and often that is what has inspired them to study law. In Cambodia, there are very few lawyers in the provinces, leaving those who live in rural communities vulnerable to legal rights abuses. The trend is for lawyers to move to Phnom Penh and build their legal career there. IBJ’s strategy was to reverse this trend by trying to persuade competent lawyers to practice in provinces. At least we now have four young, energetic and committed lawyers working in our provincial offices and effectuating positive changes.

<

<