Next Wednesday, August 4th, Kenyans from Mombasa to Busia will report to the polls in droves to vote in a referendum on a brand new Constitution. It has been a hot topic of conversation throughout the summer, with headlines and nightly newscasts dominated by speculation about whether Yes or No will carry the day. Most polls indicate that the Yes camp is holding the lead with less than a week to go, so it’s appropriate to examine what a yes vote next week could mean for the Kenyan justice system.

A Yes rally in Kisumu last month drew a crowd of supporters wearing green to show their approval of the new Constitution.

The new Constitution could represent a shift for the justice system in two ways – first, it would re-organize the structure of the judiciary and the way in which judges are appointed, and second, and more importantly, in the new and much more extensive bill of rights, the rights of the accused and the imprisoned are addressed in a much more detail. In terms of restructuring the judiciary, the new Constitution provides for the establishment of a Supreme Court, which for those already convicted opens up a new avenue for possible future appeals. In terms of the appointment process, the new Constitution provides for the approval of presidential appointments to the judiciary by the National Assembly, placing at least some semblance of a check on the president’s power of appointment. Previous administrations have been accused of giving out government positions as political favors, so with approval from the National Assembly necessary as well as a committee in place to recommend appointments to the president, the appointment process will be much more transparent.

Though this box was spotted at the post office, the new appointment procedures could help curb corruption.

More important than the structure of the judiciary are the provisions in the bill of rights for those accused and those convicted and subsequently detained. For those arrested, some of the most important clauses in section 49 are that they have the right to communicate with an advocate, the right to be held separately from those already convicted, the right to be brought before a court within 24 hours, the right to be released on bond or bail pending a charge or trial unless there are compelling reasons for them to be held, and the right to remain free from remand custody if their offence carries only a fine or a maximum sentence of six months or less. Section fifty continues by elaborating the rights contained under the heading “fair hearing,” which include the right to have adequate time and facilities to prepare a defense, the right to be represented by an advocate, the right to be informed of and to have access to the evidence being used against them, and the right to have the trial begin and end without “unreasonable” delay. Finally, section 51 provides for the rights of the detained, stating that they retain all fundamental rights outlined in the Constitution except those that are incompatible with detainment, that each person has the right to petition for an order of habeas corpus, and that Parliament shall enact legislation providing for “humane treatment of those detained that takes into account relevant international human rights instruments.”

All of these clauses speak to current problems with the Kenyan justice system, particularly those that concern the timeframe within which an accused person should have an initial appearance in court and within which a trial should begin and end. One of the primary problems under the current Constitution is that trials and appeals tend to drag on for very long periods of time for a variety of reasons including the unavailability of witnesses or the lack of proper paperwork. Meanwhile, the accused languishes in remand custody for months or years, time that is sometimes not even taken into consideration during sentencing. Section 51 could be very important in improving prison conditions, addressing the major problem of prison overcrowding in its mandate of humane treatment that comports with international standards.

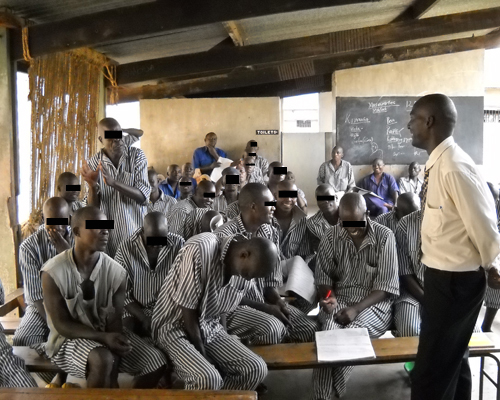

Peter Daniel Onyango, an attorney with CLEAR (Christian Legal Education Aid and Research) in Kisumu, addresses prisoners at Kibos Prison about what the new Constitution could mean for them. CLEAR was among the recipients of the 2008 JusticeMaker awards.

While the new Constitution could be an important step for the Kenyan justice system, some questions remain and some obvious ambiguities arise. For example, what constitutes “unreasonable delay” under section 50? Parliament may choose to further define the term “unreasonable” in a revised penal code, but it may also leave it undefined and leave the door open for long delays before and during trials. In addition, some implementation problems may arise. If accused persons are not to be held with those serving sentences and overcrowding needs to be relieved, much of the prison system would have to be reorganized and new prisons possibly constructed. These could prove daunting tasks, even with the four year allowance for implementation that the Constitution provides.

Even with these possible pitfalls and ambiguities, the proposed Constitution undoubtedly represents an improvement from the current regime. In restructuring the judiciary, along with other branches, and in providing a much more detailed bill of rights, the new Constitution is at least a step in the direction of much needed reform. Next week, Kenyan voters will determine whether they’re ready for that reform or not.