By Daniel Ginetty

At 6 p.m. on November 10, 2007, seventeen-year-old Sopaea finally lost his patience and stepped outside of his family’s apartment to confront his thirty-five-year-old neighbor, Karona, who had been taunting him loudly from the courtyard for the past half hour. Karona was angry because Sopaea’s dog had bitten his young son a few days before. The child was rushed to the hospital and would be fine, but his father, having passed through the phase of instinctual paternal dread for an injured child, now seethed with anger and chose to take it out on Sopaea. Of course, Sopaea and his family were sorry that their dog had bitten the little boy, even though they believed that the child had provoked their dog. They offered to pay for the child’s hospital bills, but refused to pay Karona’s counteroffer of $500 in order to avoid a civil suit. Tempers on both sides were high: the neighbors feeling uncompensated for their suffering; Sopaea’s family feeling extorted over an unfortunate accident. The pressure of pent-up emotions popped when Sopaea opened the door. Immediately he and Karona were exchanging blows and, soon after, both were in the hospital with injuries from their cathartic brawl.

In the hospital, Karona decided that he was more certain to get retribution by initiating a civil complaint against Sopaea for battery than by filing a complaint about the dog bite. He sent one complaint directly to the local prosecutor’s office and a separate complaint to the local police chief’s office. Both complaints were identical in every way except that the date of the incident stated on the prosecutor’s copy was November 10, the correct date, and the date on the police chief’s copy was November 11, a careless copying error. Due to a breakdown in communications, the police were unaware that the prosecutor was processing an identical complaint and vice-versa. The prosecutor’s version of the complaint was the first to reach a judge’s desk at the Phnom Penh Court of First Instance. The judge summonsed both parties to a trial on August 15, 2008 where, unfortunately for neighbor, this judge determined that both sides were nearly equally at fault and gave both men suspended prison sentences with no civil compensation: Sopaea received eight months, Karona, six months.

Unsatisfied with the minor victory of a lesser suspended sentence, Karona waited a few months and then secretly pushed his second, “November 11th,” complaint through the police processing procedure, as if his first complaint had never been filed and resolved. Karona could have appealed the Court of First Instance’s decision, but he did not expect a favorable result in the Court of Appeal and, by this time, the appeal period had long since expired. Luckily for him, the November 11th complaint ended up on the desks of a different deputy prosecutor and a different judge at the Phnom Penh Court of First Instance. Even though the judge has been informed by Sopaea’s former lawyer about the first verdict, he decided to trial it again. This court held a trial on November 10, 2010, but Sopaea did not show up because he never received the summons for the second trial. Since he did not appear in court, however, the judge only heard the neighbor’s side of the story and only recorded into evidence his hospital records. Unsurprisingly, he gave Sopaea a three-year sentence in absentia. Moreover, since the court had summonsed Sopaea in accordance with the code of criminal procedure, this verdict counted as a non-default judgment, meaning that Sopaea’s only recourse was to the Court of Appeal; he could not petition the Court of First Instance to rehear the case with him presenting his own side of the story.

The court issued an arrest warrant for Sopaea, but the police only had his old address. Almost a year before this verdict, his father, a soldier, was assigned to a different military barracks in Phnom Penh and the family moved to a new apartment complex to stay close to him. With bigger fish to fry than a young man convicted of assault, the police did not put much effort into finding him. Thus, Sopaea had no idea that he had been convicted and was shocked, to say the least, when police finally caught up with him in April, 2012. They tore him out of his mother’s arms and took him away to serve his three year sentence.

He was incarcerated in Phnom Penh’s Correction Center 1 where his mother was able to visit him often because the prison is close to the family’s home. She paid 6,000 Riels to see him through bars for thirty minutes because she could not afford the price of a “premier” visiting ticket, which would have allowed her to sit with him in an open meeting room. After three months, prison officials shifted him to Correction Center 4, in Pursat province, meant to provide a transitional environment for those convicted of less serious crimes. His mother could no longer afford to travel the distance to visit him. All she could do was send him noodles and books back with CC4 guards who had family in Phnom Penh, whenever they were in the capital visiting. His experience, however, did not measure up to the hype.

Sopaea was in CC4 for ten months and his experience there did not live up to the hype about its humanitarian, rehabilitative focus. He lived in block B2, in a 6X11 cell with fifty other convicts. He remembers often praying for rain to fill the pond adjacent to the prison yard because there was never enough water to wash with. He wanted to enroll in vocational classes offered by one of the prison NGOs, but he could not afford to pay the ten dollars which the guards—without the NGO’s knowledge—were asking as the price of admission.

Meanwhile, Sopaea’s mother was desperately asking relatives and friends how she could get her son out of prison early. One of them told her about IBJ and she called the Phnom Penh office on August 17, 2012. Mr. Vandeth, one of the longest serving defense lawyers in Cambodia and the country manager for IBJ Cambodia, accepted the case. That fall, when he traveled out to CC4 for the standard pre-trial client interview, Sopaea told him about the discrepancy between the two complaints. Mr. Vandeth knew immediately that Sopaea did not belong in prison; the second judge clearly had not done his due diligence and had flouted criminal procedure. The only difficulty he anticipated was the fact that the appeal court would only have the one-sided evidence on record from the second trial at the Court of First Instance.

Sopaea had to place blind faith in Mr. Vandeth, because he could not attend his April 25, 2013, appeal either, although he had no choice in the matter this time. The CC4 prison officials demanded a $200 transportation fee, at least twenty times the average bus ticked from Phnom Penh to Pursat and much more than Sopaea could afford. This practice of extortion is common, both on account of the guards’ impunity and the lack of funds for gasoline in most prison budgets. When convicted persons are not represented by a lawyer (an accused is not guaranteed a lawyer in cases of non-juvenile, misdemeanor offenses, which still may carry five-year penalties), the situation is even more dire because they will almost necessarily lose their appeal if they do not appear to represent themselves, even though the reason for their absence is the prison administration’s own failure. On the other side of the coin, those who are fortunate enough to find transportation from their provincial prison to Phnom Penh are often stuck there after their appeal trial without transportation back home. Indeed, if an accused person travels to Phnom Penh and loses his appeal, he may just be stuck there in a new prison environment with fewer or no opportunities to see family.

Sopaea had to place blind faith in Mr. Vandeth, because he could not attend his April 25, 2013, appeal either, although he had no choice in the matter this time. The CC4 prison officials demanded a $200 transportation fee, at least twenty times the average bus ticked from Phnom Penh to Pursat and much more than Sopaea could afford. This practice of extortion is common, both on account of the guards’ impunity and the lack of funds for gasoline in most prison budgets. When convicted persons are not represented by a lawyer (an accused is not guaranteed a lawyer in cases of non-juvenile, misdemeanor offenses, which still may carry five-year penalties), the situation is even more dire because they will almost necessarily lose their appeal if they do not appear to represent themselves, even though the reason for their absence is the prison administration’s own failure. On the other side of the coin, those who are fortunate enough to find transportation from their provincial prison to Phnom Penh are often stuck there after their appeal trial without transportation back home. Indeed, if an accused person travels to Phnom Penh and loses his appeal, he may just be stuck there in a new prison environment with fewer or no opportunities to see family.

Sopaea’s mother watched the proceedings in the Court of Appeal and then went home to wait for the verdict to be issued. The Court overturned the Court of First Instance’s conviction on May 2, and Mr. Vandeth called Sopaea’s mother to tell her the good news. The next day she began a journey up to CC4 in Pursat to pick up her son and bring him home after fourteen months of being separated from him. The entire ride took her ten hours, three-quarters in a taxi and the rest on the back of a moto-dop. Even after having travelled all that way, when she arrived her ordeal was not yet over as the guards demanded a bribe that she could not afford and she was forced to spend the night sleeping on the floor of a nearby Buddhist pagoda, planning her next move. Fortunately, the guards on duty in the morning reduced their asking price to fifty dollars, which she was barely able to pay.

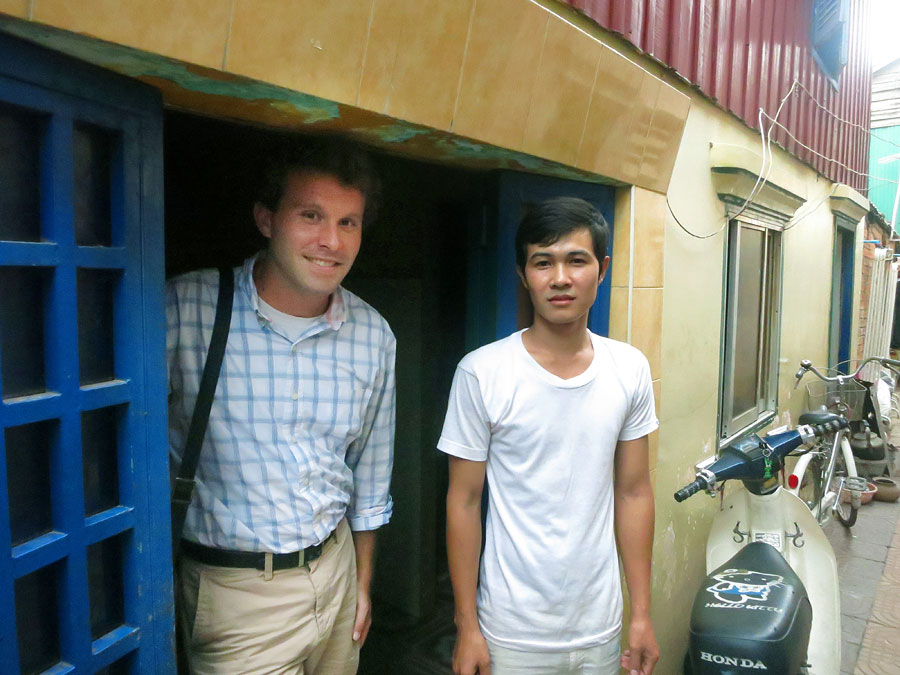

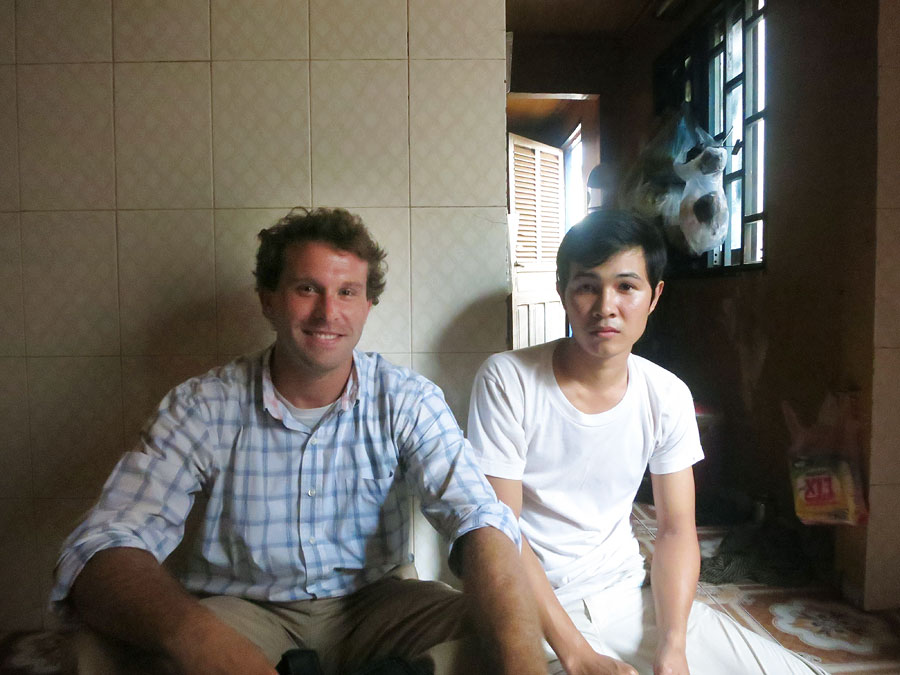

Needless to say, she forgot all of those obstacles once she saw her son and held him in her arms again. She took him to the pagoda where she had slept to receive a blessing from the monks there and, on returning to Phnom Penh, prayed again in the family’s usual pagoda. Of his two siblings, Sopaea’s older brother lives on his own, but his younger sister is still in school; in fact, she was out taking the grade-five exam on the day I interviewed him and his mother. The mother makes a meager living, selling sweets to exhausted factory workers at the end of their day, her husband is still employed by the military, and Sopaea works in a PepsiCo manufacturing factory. The family now lives in a small apartment on the corner of a narrow alleyway. The dog who set these events in motion has since died of natural causes, but they have nine cats, thanks to a recent generous litter. Knock on wood, no one has been scratched, yet.