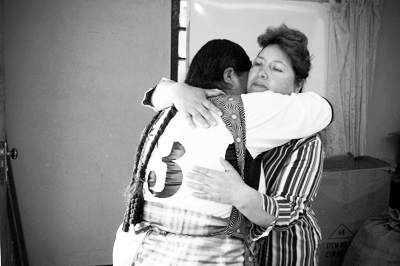

A young child wipes the tears from her mother's eyes. The woman is recounting her story and how through JusticeMaker Marisol, she has some hope for her situation. She is currently being held in Obrajes, a women's prison in La Paz, Bolivia, along with her five youngest children. -Ruth Lloyd

The rain is pouring down outside and it is cold inside the unheated concrete room.

The room has stacked plastic chairs at one end, ancient-looking computers pushed against the wall and covered in protective plastic dust jackets.

Marisol has told us they offer classes in the room, including basic computer classes.

Marisol and Eliana Barragan, acting as a translator, sit at a small square plastic table, as women they are interviewing take take turns in seats at the table.

We have been in the prison for six hours, and it has been exhausting.

I feel cold and drained of energy, and I can tell I am becoming numb – a natural reaction perhaps to so much sadness and so much emotion.

Yet Marisol is still animated, meeting each interviewee with compassion and she listens attentively to yet another woman tell her story, a difficult story because it is a woman seeking her help with a new problem, not one of the many women Marisol has met through her Justice Makers workshops who she already works to represent.

This happens constantly while we are in the prison walls.

When Marisol leaves the room to find another of the women we are to interview, a middle-aged woman, well-dressed but walking with a cane, comes in to look for her. The inmate holds a folder full of papers, and she wants to speak to Marisol.

When we leave the room, into the common courtyard area of the prison, women approach Marisol to ask for her help with their case or specific concerns.

One woman rushes up to thank Marisol, hugging her and then us as well. Marisol has helped the woman secure a day pass in order to attend the funeral of her father, who recently passed away. The woman’s eyes are red and swollen, and she has been waiting anxiously while Marisol worked on the problem, meeting with a judge and obtaining required papers. Marisol had to cancel our morning appointment to work on the case this morning before we came to the prison, and we had then waited for her in the courthouse, as she finalized the permissions, which thankfully, she obtained.

Then we took the minibus which brought us here, to Obrajes, a women’s prison located in an upscale neighbourhood in the city of La Paz.

After handing over our cell phones and identification documents, our bags were given a quick search and we went through a second, unassuming doorway and emerged into the prison proper.

We are immediately introduced to a woman I will call Tasha, she is an elected official amongst the inmates, who helps to manage the inner workings of the prisoners, and she greets us warmly.

The open courtyard within the prison is bustling with people, inmates, visitors and children give the place a much more social and relaxed atmosphere than I had at first expected.

I have been restricted from taking photos anywhere but inside the interview room, and so I leave my camera in my bag as we watch the children play and women busy themselves.

Two women sit next to each other on the cement walkway, crocheting industriously, others chat in groups, some sit behind small kiosks, selling food, snacks and drinks.

The women in the prison can earn money at various jobs, and the women who have been there the longest usually fill these positions, creating somewhat of a hierarchy within the prison, according to Marisol and Tasha.

But we are not in the prison to learn about its inner workings or the conditions so much as we are there to speak directly to the women who Marisol has been working with, and hear their stories in person. To learn how her work teaching prisoner’s their human rights and how to work within the justice system to ensure their rights are being upheld can change these women’s lives.

Which is what we have spent the six hours within the prison doing.

Women come in, sit down and answer our questions about their situations and how Marisol’s workshops have helped them, how her assistance is changing their situation or simply their perspective, giving them something they had far too little of – hope.

A detainee wipes her eyes as Marisol (right) listens to her recount her story and the difference Marisol has made. The woman and her sister have been held on charges related to a police drug raid of her house. She had rented part of her house to a man making drugs out of desperation for money. The police raided the drug lab while her sister, who knew nothing of the illegal activity, was visiting. Both remain in prison, one year after being detained, without a trial date. -Ruth Lloyd

The only two women who remain dry-eyed in their gratitude for Marisol’s work and the recounting of their difficult circumstances are two immigrant women from Ecuador, caught for robbery after they ran out of money on their trip to Bolivia.

The two women seem defensive, and Marisol explains they are heavily discriminated against within the prison because they are not only foreigners but also because they are lesbians, and a third woman captured with them is of African descent.

But the five other women we interview all shed tears of both gratitude and pain as they speak to us.

Every woman we speak to is incredibly grateful for the help Marisol has provided them, assisting them in forwarding their cases and ensuring their rights are being upheld.

In most of the cases, Marisol is working to obtain conditional releases from pre-trial detention, which can be for as many as three years in some cases.

While there are supposed to be limits on how long prisoners can be held without trial, these limits are not always adhered to, and prisoners can be lost in the system, unaware they had the right to at least conditional release before a trial. This is the ignorance Marisol is working to change.

“When [Marisol] comes, it is joy for us,” said one women (translated).

The woman explains how before Marisol took her case, she and her sister were unsure of where to turn or what they might be able to do.

They report they were defrauded by one lawyer who promised to help, but after being paid a retainer, did nothing on their case, a reportedly common practice according to Marisol and may of the prisoners we speak to.

One of the sisters was visiting the other when a drug lab was raided in her sister’s home, in a part of the house which had been rented out to a man to help support her, as she was in debt.

The one sister was aware of the drug activity in her own home, and had reportedly taken the risk due to debt, but had not told her sister. This is what they tell us, explaining it was only tragic timing on the sister’s part to be there the night the raid took place.

“I thank God for giving me the opportunity to help you,” said Marisol (translated) to the sisters.

Some of the women admit they were first reluctant to trust Marisol because of previous warnings or experiences of unethical lawyers. But by teaching them their rights, the detainees become less reliant on the advice of lawyers and more capable of ensuring any lawyers they do hire are fulfilling their obligations. Another woman tells us how she was arrested because her husband fathered a child with his stepdaughter (the interviewee’s eldest child) and she didn’t report him. She seems to have lived in fear of him, saying he abused her, and she also had five other children at home he was the sole supporter of.

Uneducated and poor, she did not feel confident enough in the system to help her, so she and her five younger children are now in prison for her husband’s actions (he is also in prison somewhere else).

Her youngest child wipes tears from her mother’s eyes as she tells us her story.

The stories are tragic, and heart-wrenching, filled with sadness and regret and I am glad when afterwards we step back through the door and retrieve our identification and cell phones.

We have the luxury of leaving, and I am at least comforted by the knowledge Marisol will be back.